Frederic Church (1826-1900) was one of America’s most significant and talented 19th-century artists. He was a prolific and successful painter whose life was so well documented that it would be easy to see him as a fixture of the well-worn and over-rehearsed art history books about the Hudson River School. Maybe.

Then again, maybe not.

I absolutely believe Church left his heart here, because in Maine, he found the romantic soul of America. And the 25 works in “Maine Sublime” at the Portland Museum of Art make a good case that Church was a great Maine painter.

Sure, some high-strung art historians might take twitchy issue with that, but the guy bought 400 acres of land on lake Millinocket; in two institutions alone, there are more than 200 of Church’s paintings and drawings of Maine; Church framed and displayed a disproportionate number of his Maine scenes in his other home; and the last painting he ever signed — which, amazingly, is in the PMA show — was an image of Katahdin made as a gift for his wife.

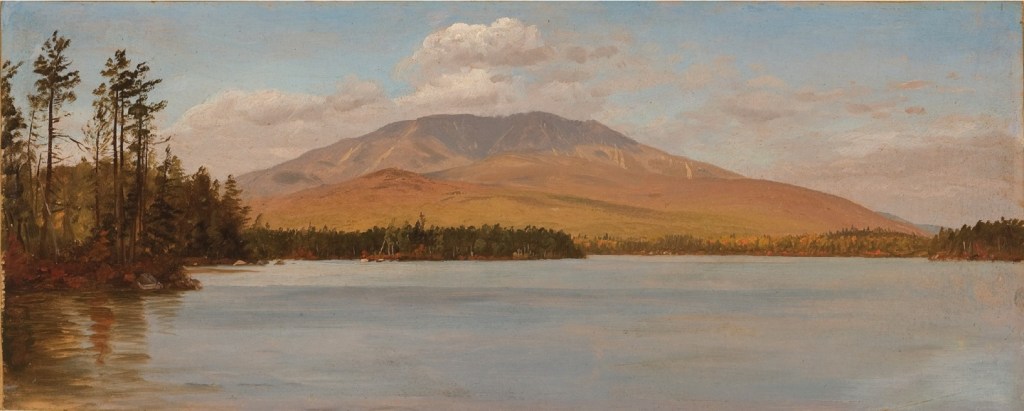

The comparison of that gift — “Mount Katahdin from Millinocket Camp” (1895) — to the smaller “Mount Katahdin from Upper Togue Lake” (circa 1877) shows the fundamental split in Church.

The 1895 canvas is a Hudson River School-style painting. Its visual depth is dedicated to a vast space, and even the middle ground is very distant; the scene is lorded over by an awesome giant (Katahdin), and the sublimity of the experience is put in perspective by a tiny human figure in a canoe at the bottom/front of the painting.

The smaller image — likely painted on site — is more geared towards composition and structure. Instead of the clear and atmospherically incalculable sky of the larger work, it features a set of lively clouds that presses the mountain towards us.

The water comes to the front edge of the image, so the eye enters from the repoussoir trees on the left and slides past a further dark line of shore before settling on the autumnal foliage of the far shore of the lake — the image’s most beautifully painted passage.

In short, the smaller piece is dedicated to being a more sophisticated painting, while the Hudson River School-style piece is more about pulling our heartstrings. Both are great, but I think the smaller piece is far more sophisticated and complex. It paves the way for painting in Maine.

“Maine Sublime” shows us an artist who was dedicated to his vision of Maine aesthetically, spiritually and artistically. Ironically, the easiest part of this to describe is the spiritualist part.

Maine seemed to represent for Church the soul of the American landscape, particularly through the coast at Mount Desert Island and the mountain vistas around Katahdin.

Church’s aesthetic take on Maine was subtle and strange. While his mentor, Thomas Cole (who, along with Thoreau’s writings pointed Church to Maine), painted with relatively uniform technique over any image, Church would vary his approach within a single painting.

This point has been noted by folks interested in metaphorical content about national division around the Civil War, but to the detriment of some very basic points about painting — and landscape in particular.

For example, Church’s “Twilight, A Sketch” is about the size of a sheet of paper. It has a dark band of land (a forest, a lake and distant mountains) along the bottom half and a thin clear band of cloudless golden sky in the far distance that divides the terra firma from one of the wildest red sunsets ever painted.

Church exhibited this study (the monumental version of which is at the terrific Cleveland Museum of Art), and it’s been interpreted as a metaphor about national disquiet on the verge of war.

But as a painter working with new cadmium pigments, Church seems to have been addressing the distinctions between light and color. The colors of the sky, after all, are effects of reflected light ,while the green of leaves is endemic to their trees.

John Wilmerding mentions the new cadmium pigments several times in his excellent essay in the beautiful catalog that accompanies the show, but without explaining why. Any painter can tell you cadmium pigments are the most intense colors because of their extreme opacity (which makes glazing basically impossible). Church uses cadmium pigments to make some of his sunset skies more solid than the land over which they reign. The saturated color might have been extremely popular, but it was a radical break for painting.

Church was a prodigy, and this is particularly evident in his drawings. While many are clearly intended as designs for paintings, some are breathtaking on their own.

The drawing of a Mount Desert Island lumber mill, for example, is technically stunning, but also far more pictorially complex and sophisticated than the painting made from it.

Church could do it all. He could draw and handle a brush with virtuoso skill. He was a brilliant and inventive colorist. He had a sophisticated eye for complex construction. And while he savored the spiritual solitude of Maine, he actually liked people and respected his audience.

Church may have died more than 100 years ago, but “Maine Sublime” is fresh and full of discovery.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.